Embracing uncertainty: How workplace design has changed

Working is different now, and yes, I know you are hearing that expression a lot these days. You’re probably overwhelmed by the volume of opinions, either good or bad, about remote working along with the rise of activist employees demanding that their performance and productivity be the measure of their contributions rather than presenteeism.

Working is different now, and yes, I know you are hearing that expression a lot these days. You’re probably overwhelmed by the volume of opinions, either good or bad, about remote working along with the rise of activist employees demanding that their performance and productivity be the measure of their contributions rather than presenteeism. A quick Google search puts the number of results at a staggering 629,000,000 in the business ether since March of 2020. I know I’m sick of hearing from those who think they know what work will be like going forward. I don’t know and I’ve decided to embrace uncertainty. I’m making the conscious decision to be open to the possibility of being wrong through experimentation and discovery. I think it’s OK if it’s messy.

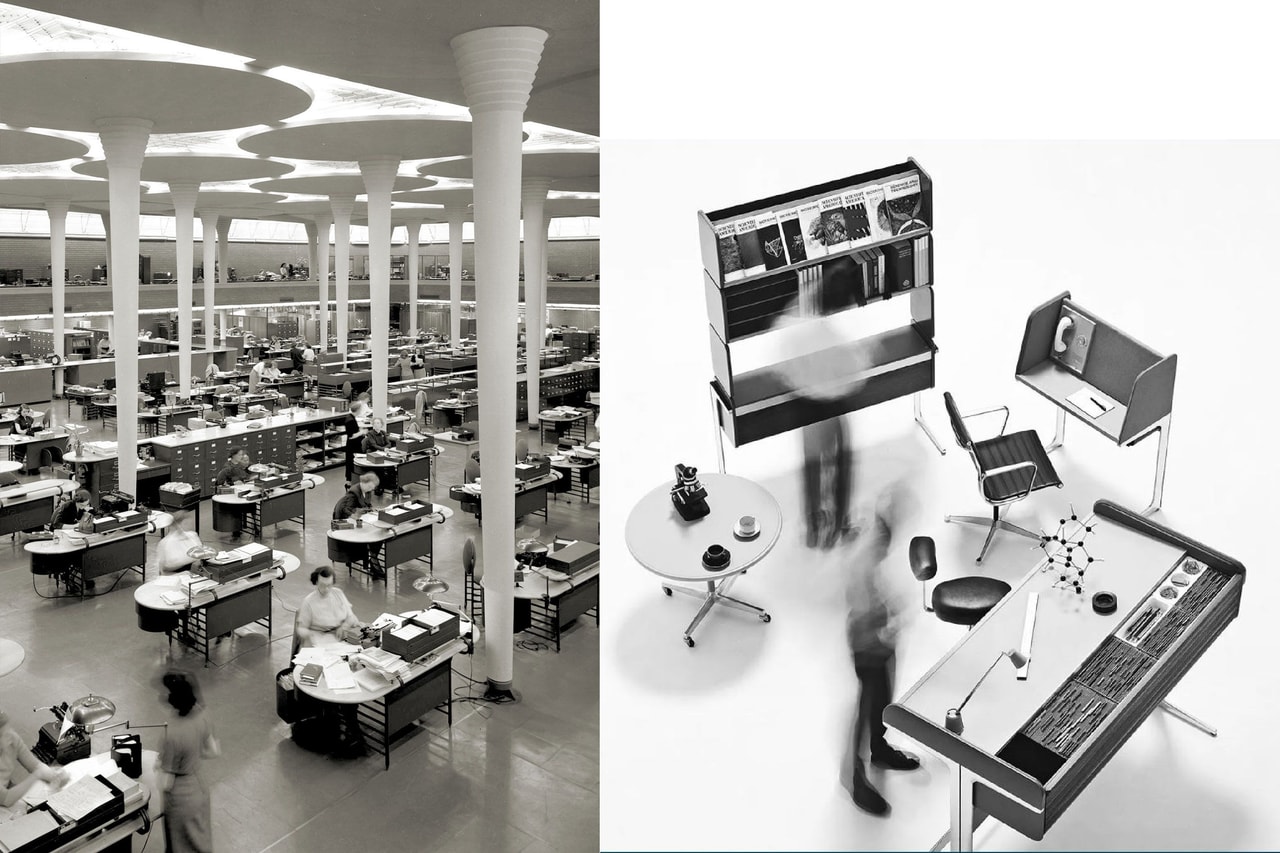

Working was different back then too. In 1939, Frank Lloyd Wright completed the SC Johnson Wax headquarters in Racine, Wisconsin – the workplace of the future with its cathedral-like open 'workroom'. 25 years later, Herman Miller launched the Action Office line of workstation cubicles in 1964 – a radical departure from the private office and typing pools of the previous generation. A few years later in 1968, BDP opened its studio in Preston in the UK. The space was designed around "Burolandschaft” - the Office Landscape principles developed by German brothers Eberhard and Wolfgang Schnell. The thinking prioritized informal, organically planned spaces that had been made possible by this new system of furniture. All these watershed moments had profound impacts on workplace design. With the exception of the banking and legal professions who cling to hierarchical private offices, every current worker is part of the open office generation. Unfortunately, it seems that we lost the organic landscape essence in pursuit of maximum density. You may be familiar with Vox, an online news channel whose tagline is ‘understand the news’. In September 2022, a Vox producer by the name of Phil Edwards published a video documenting his experience working in the greatest workplace: the SC Johnson workroom. The piece is informative about the space, irreverent in tone and ultimately ironic as Edwards comes to the realization that he was just staring at a laptop screen and that “being in an amazing office space wasn’t a real thing without any people around…the space didn’t matter without the people, it’s just a background”.[1] It may be counter-productive for me as a designer to say that space doesn’t matter, but let’s take it from Phil Edward’s perspective: he was disappointed to conclude that a magnificent space meant little despite its reputation because it didn’t feel like a working space without his colleagues.

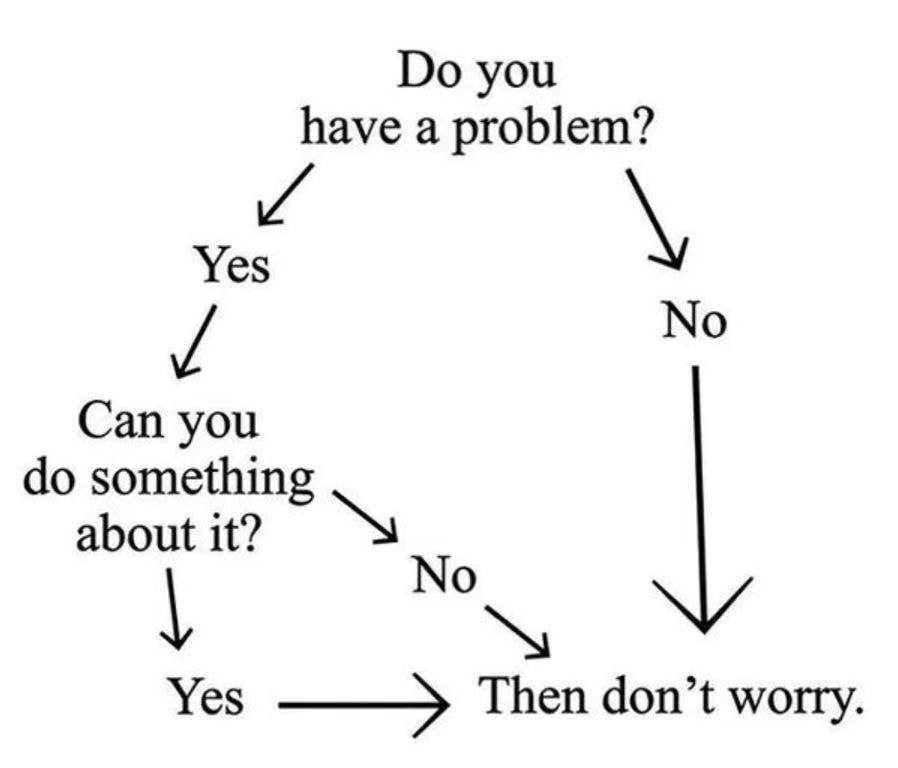

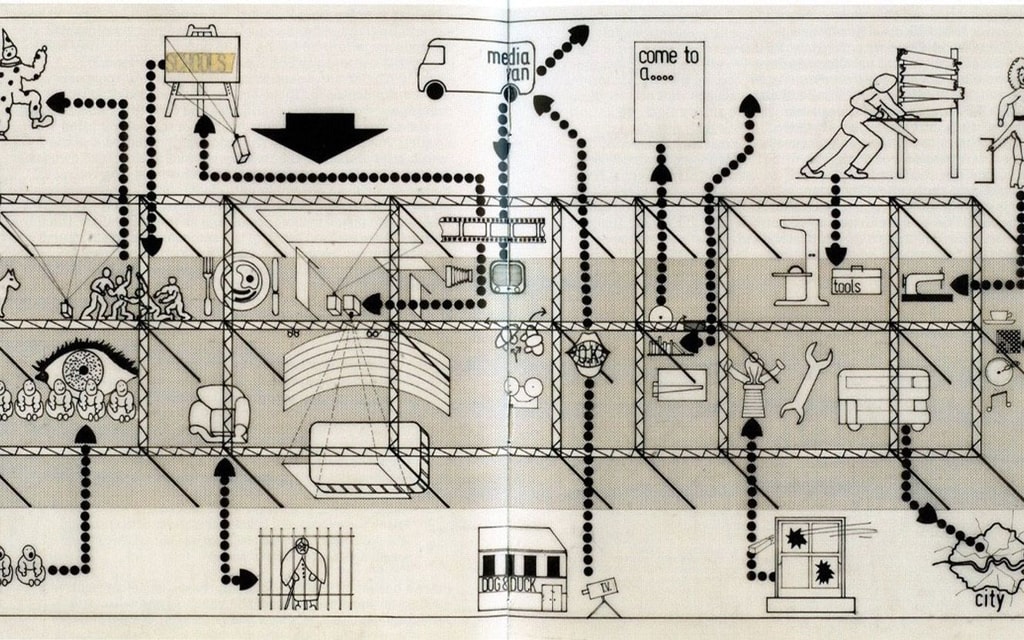

We have just completed what I am un-humbly going to say is a magnificent workspace in The Well in Toronto. Does it matter? To be honest, not really, but I do think the design of the space plays an important role in accommodating choice. Flexibility, choice, variety – all words we as designers use a lot when we’re trying to explain the planning of spaces that can morph over time and offer people more than they were expecting. Rather than saying flexibility, I prefer to call it designing for uncertainty. Uncertainty means that there are possibilities of which none of us have thought, something design must be open to. Design should be a bit messy to allow a space and its contents to be changed by those who use it daily. The English architect Cedric Price (1934 – 2003) engaged in the practice of serious fun. “He demanded that design take on the mess, the mistakes and perceptibly inadequate, imperfect conditions of aspirations for short-term occupancy and similarly unknown quantities…Serious fun is the practice of designing for those conditions that are approximate and change over time.”[2]

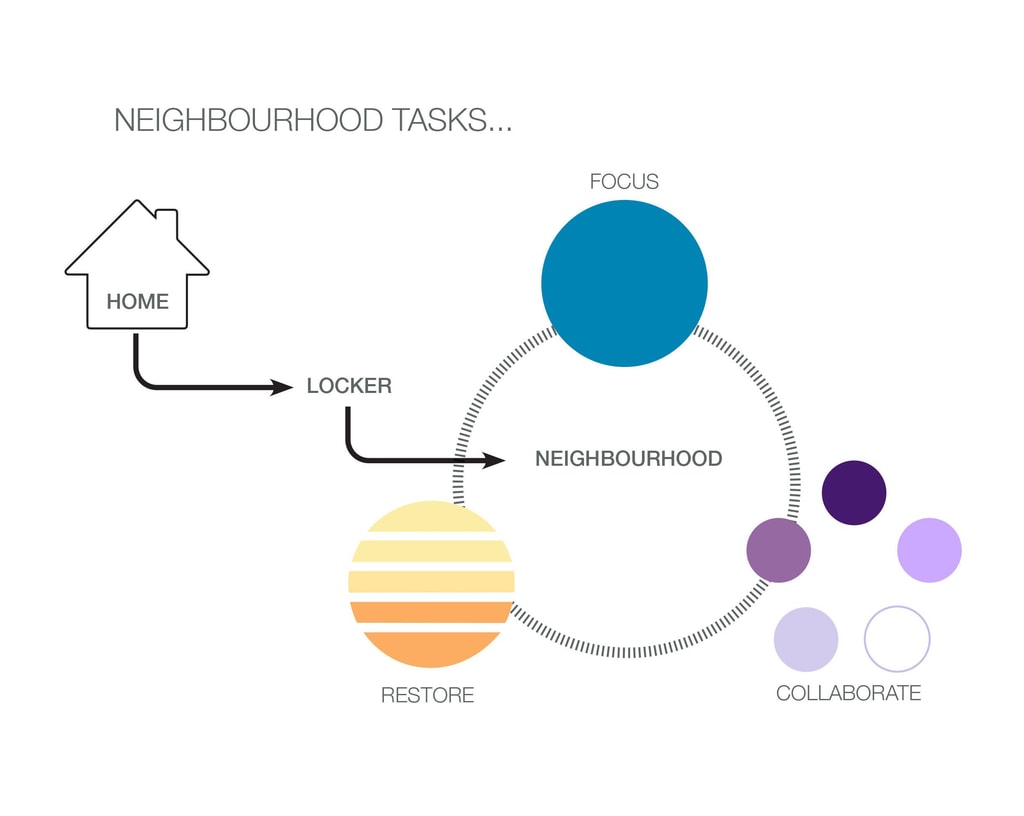

We started the design of this studio in 2019 with modest ambitions to increase collaborative space and move us from an open to a more agile workplace that accommodates different working styles and choices. The location came with increased, democratic access to natural light and great views, so we have improved the most essential experiential needs. We gathered a lot of information through observational, ethnographic and opinion surveys, as well as town halls and design charettes to create goals for the schematic design. All those conclusions had to be re-evaluated and reset once the pandemic hit. The instant change to remote work allowed us to be bold and not let the crisis go to waste. We changed the design approach to what would bring people back to a physical space from only trying to accommodate a total number of people. We needed to separate the actions of focus, collaboration and restore and take territorial ownership of space out of the equation. The attitudes had shifted from staff politely asking for more flexibility around where and when they worked to becoming the first question by candidates in recruiting conversations. In two years, almost every organization had become a distributed workforce.

We landed on the organizational concept of a neighbourhood. Design teams would have a home base that accommodated those core functions of focus, collaborate and restore, but taking the urban context further, you can travel from your neighbourhood to someone else’s for a visit or spend the day in the community hub. Through a combination of Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI), MS Teams telephony and the move exclusively to laptops, no one is tied to a desk anymore. Not everyone is comfortable letting go of the notion of ‘my desk’ and it may take them some time to watch their peers experiment and discover new ways to work that might be better than what they are used to.

A robust Wi-Fi network, distributed power and additional screens throughout the space make any seat or standing surface a workstation. We are hopeful that everyone gets to a comfort level with uncertainty, shifting mindsets away from a feeling of uneasiness to one of empowerment though the exercise of personal choice. The workplace of 2019 infantilized us as if we were in primary school with rules dictating our every move and attendance. We’ve matured into university students with autonomy of choice, each responsible for our own delivery and freedom to move around campus to realize those results.

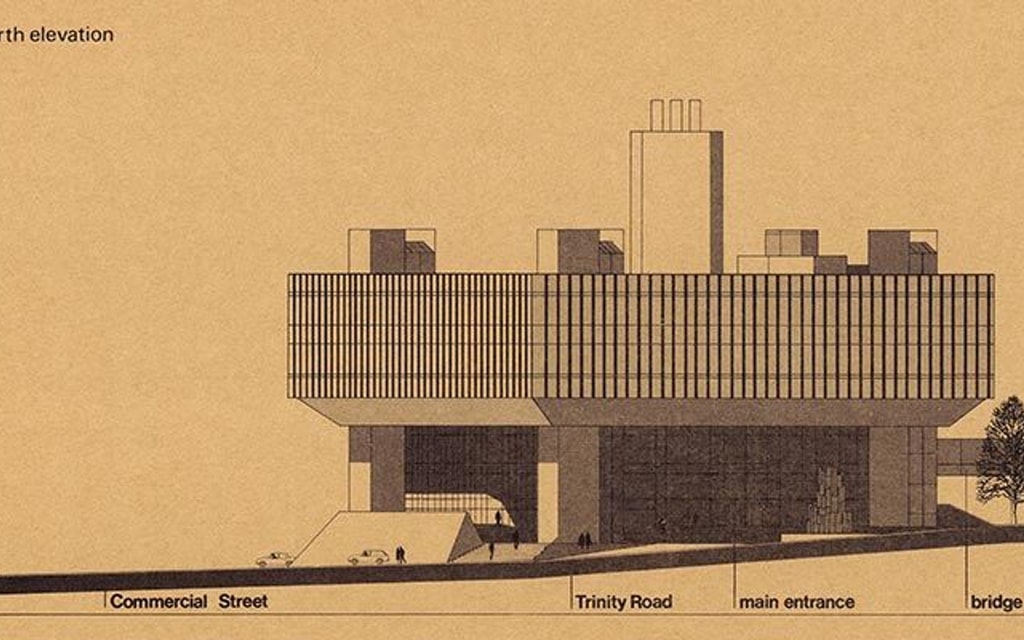

BDP Quadrangle’s culture is one of innovation and problem solving. We are currently experimenting with AI learning opportunities to reduce repetitive tasks to further free us for creative thought and application. Our opportunity to explore working differently is a key part of that innovative problem-solving spirit. Is it time to go back to the future and rediscover the egalitarian and organic (both planning and planting) working landscapes of the 1968 BDP Preston studio or our design of the 1974 Halifax HQ?

The one thing I know for sure is that I don’t know if we got it right. We’re adopting a wait and see attitude to allow things to be hacked or changed over time. We’ll let you know how messy and different are working out for us – stay tuned.

[1] Phil Edwards, “What it’s like to work in the world’s greatest office” Vox 2022

[2] Sarah Hardingham, “On the visible spectrum” Serious Fun, Architectural Digest 2022

Cover Image -- Jeff Parrott, Oil on Canvas, 2009