#{Title}

#{Copy}

Modern medicine is miraculous.

ANDREW SMITH

Its ubiquity in the developed world masks its extraordinary and ever increasing ability to save lives and cure painful and debilitating conditions. Its synthesis of care and science represents one of humanity’s highest achievements, yet many of the buildings which house modern medicine do not reflect the noble endeavour undertaken within them.

There are understandable reasons for this. It is very easy for an organisation procuring a hospital to be overwhelmed by scale, complexity and the need for efficiency and cost effectiveness. The resulting hospital buildings can still treat patients’ conditions but ultimately fail to lift their spirits.

There is a need for spaces which allow caring health professionals to help patients come to terms with their illnesses, the processes that they must undergo and their feelings about them - an issue acknowledged and addressed by the objectives of the Maggie’s Centres movement.

A new generation of hospital projects is making more overt attempts to address this need. BDP has achieved this by designing a portfolio of hospitals in response to the needs of the individual patient, visitor and member of staff. An experiential approach of ‘how will it feel?’ rather than a more conventional architectural perspective of ‘what will it look like?’ or ‘how will it work?’ Such an approach permeates every aspect of our designs, engendering a sense of place, from the macro level of the city to the micro level of the individual room.

A new generation of hospital projects is making more overt attempts to address this need. BDP has achieved this by designing a portfolio of hospitals in response to the needs of the individual patient, visitor and member of staff. An experiential approach of ‘how will it feel?’ rather than a more conventional architectural perspective of ‘what will it look like?’ or ‘how will it work?’ Such an approach permeates every aspect of our designs, engendering a sense of place, from the macro level of the city to the micro level of the individual room.

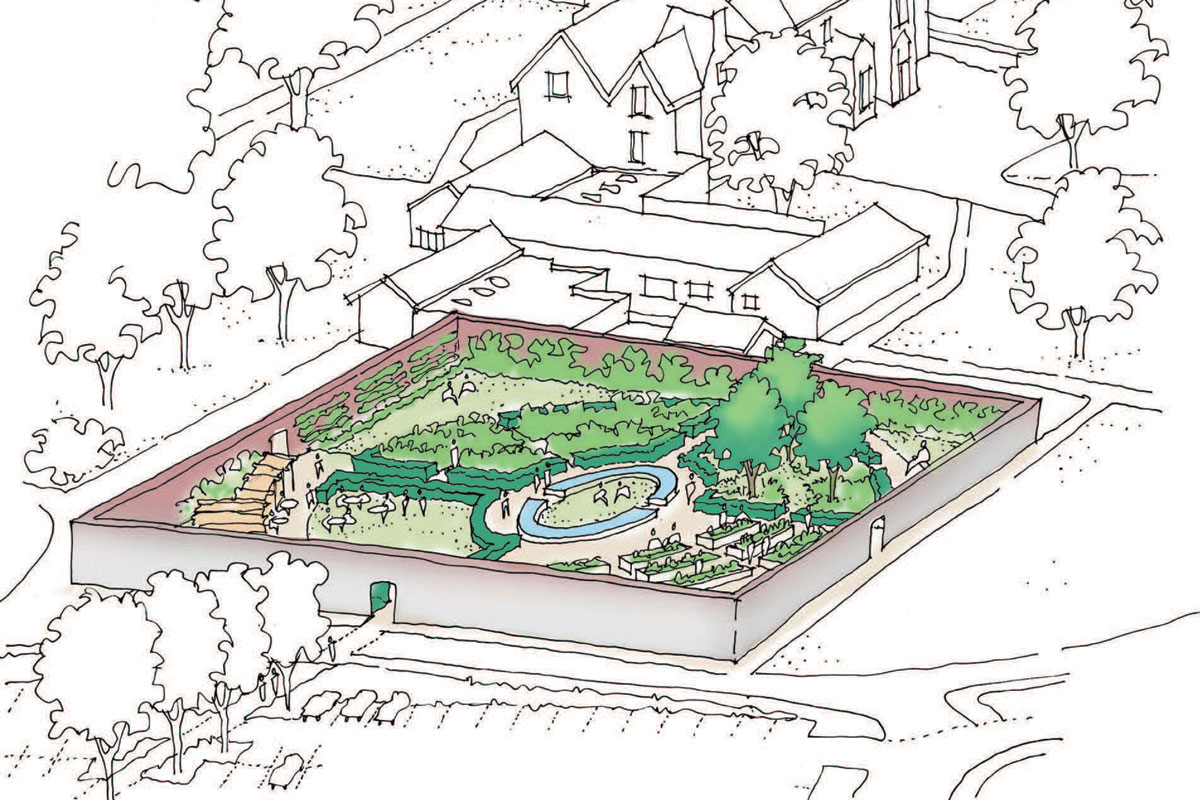

It begins before the patient even reaches the building. Rather than being isolated from the city, hospitals should be part of them seamlessly integrated into their routes, spaces and vistas. They need to be true civic buildings, reflecting their community’s pride in them and their staff.

Patients attending hospital are already feeling anxious about their health so the building design shouldn’t exacerbate matters by making it difficult to find the entrance. It should actively ease the process of arrival and navigation with the provision of vehicular and pedestrian circulation scaled more akin to that of an airport or train station. Simple wayfinding clues in the layout of the site and the form of the building should lead people intuitively to their destination.

The experience of staying in hospital can be very isolating. Hospitals, therefore, need to be designed so that patients perceive that they are still part of life, maintaining physical and visual contact with the outside world and with opportunities for social interaction encouraged within the building. Spaces of varying scales and building elements which maximise openness and transparency allow patients to see staff and, when they want, to see other patients. Staff equally need to see one another as they move around the building and in restaurant settings to promote team cohesion and the cross fertilisation of ideas between staff, students and researchers.

Conversely at other points in their hospital stay patients may want privacy. This applies particularly in the ward environment where the provision of single bedrooms can fundamentally change the sense of ownership of space so that the bedroom belongs to the patient rather than the hospital and staff are encouraged to ask whether it is convenient to enter. Patients can feel at their most vulnerable during the transfers to and from surgery and typically will not wish to be observed by the public at that time. This can be achieved with a carefully interlaced design for the hospital’s circulation to separate public, patient and logistics flows, simultaneously supporting flexibility and security.

A sense of claustrophobia associated with being trapped inside a very big hospital building is a potential consequence of the large plan area which many hospitals cover. Consequently hospital buildings need to be articulated as a series of individual linked elements that function efficiently, and allow daylight to flood into public, patient and staff spaces.

Recovery and a sense of wellbeing need to be supported by the ability to sleep whilst staying in hospital. One of the most frequent obstacles to this is the level of noise from mechanical ventilation, equipment alarms and the conversations of staff and other patients. It is therefore essential to achieve a quiet acoustic environment, through space planning, acoustic insulation and absorption.

HOSPITALS NEED TO BE MUCH MORE THAN MACHINES FOR TREATING; THEY NEED TO BE REAL PLACES OF HEALING, A SYNTHESIS OF PATIENT FOCUSED CARE AND PATIENT CENTRED DESIGN, WHICH SAVE LIVES AND HELP MAKE LIFE MORE WORTH LIVING FOR EVERYONE THEY TOUCH.

Hospitals are traditionally associated with unpleasant disinfectant smells. Whilst effective infection control measures remain crucial, the engineering design needs to achieve a fresh air ambience in the heart of the building. In bedrooms, patients should have the autonomy of control over their environment either through mechanical or natural ventilation.

Although the provision of healthcare is a very serious business, hospitals benefit from elements that are just for fun such as art programmes and mega-graphics which amuse and distract patients when they are bored and anxious.